Mai fidarsi delle apparenze. I fenomeni naturali studiati dalla fisica alle volte ingannano il buon senso. Per esempio la luce che illumina queste parole nasconde un segreto: appare “bianca”, in realtà è composta da tanti colori. Ci sembra di essere fermi eppure sfrecciamo nell’Universo con una velocità di migliaia di centinaia di chilometri all’ora. Oppure prendiamo il pesce d’acqua dolce Arapaimas gigas detto anche pirarucu. Vive in Sud America, è uno dei più grandi al mondo e può superare i 100 chili di peso e raggiungere i 2 metri di lunghezza. Nelle acque in cui vive, si aggirano i piranha, i cui denti appuntiti riescono a forare il cuoio o le ossa come se fossero di burro…

Never trust appearances. Natural phenomena studied by physics sometimes deceive common sense. For example, the light that illuminates these words hides a secret: it appears "white", it is actually composed of many colors. Or there seems to be firm and yet we move in the universe with a speed of hundreds of thousands of kilometers per hour. Or take the freshwater fish Arapaimas gigas also called pirarucus. It lives in South America, is one of the largest in the world and can exceed 100 pounds and reach 2 meters in length. In his fresh water, roam the piranhas, whose sharp teeth can puncture the leather or the bones as if they were made of butter.

Mai fidarsi delle apparenze. I fenomeni naturali studiati dalla fisica alle volte ingannano il buon senso. Per esempio la luce che illumina queste parole nasconde un segreto: appare “bianca”, in realtà è composta da tanti colori. Ci sembra di essere fermi eppure sfrecciamo nell’Universo con una velocità di migliaia di centinaia di chilometri all’ora.

Oppure prendiamo il pesce d’acqua dolce Arapaimas gigas detto anche pirarucu. Vive in Sud America, è uno dei più grandi al mondo e può superare i 100 chili di peso e raggiungere i 2 metri di lunghezza. Nelle acque in cui vive, si aggirano i piranha, i cui denti appuntiti riescono a forare il cuoio o le ossa come se fossero di burro.

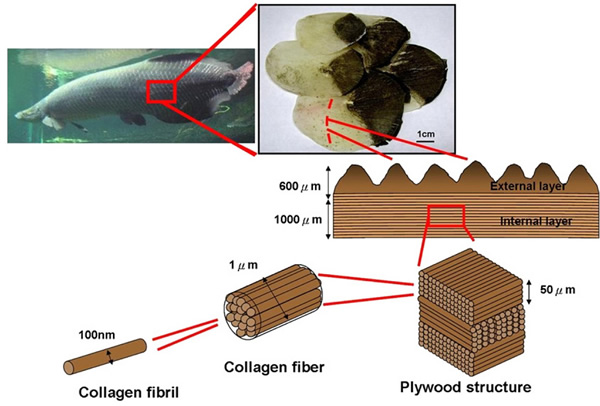

Ma i pirarucu non temono i morsi dei loro colleghi: la loro pelle potrebbe resistere fino a una pressione pari a quella esercitata da un peso di 98 tonnellate su un solo centimetro quadrato. In pratica una pressione doppia di quella che può sopportare lo scafo di un sommergibile nucleare. Perché? Per scoprire il mistero, un piccolo campione della loro pelle è stato irradiato in un acceleratore di particelle.

Marc Meyers del Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory e il professor Marc Meyers della Jacobs School of Engineering alla University of California di San Diego studiano da quasi quattro anni la pelle dell’Arapaimas e hanno scoperto come e perché questi pescioni riescano a sopravvivere ai morsi più violenti. Innanzitutto la pelle non è morbida come quella di una trota ma è coperta di scaglie dure, disposte come le tegole di un tetto. Sono scaglie mineralizzate, simili in composizione allo smalto dei denti. Sembra questo il loro segreto. Invece la verità è sommersa. Le scaglie, come un cioccolatino ripieno, nascondono un cuore morbido. Si tratta di filamenti di collagene, una proteina elastica e resistente, disposti in modo particolare:

Il collagene è una delle proteine della giovinezza: una pelle fresca, tonica e compatta ha abbondanti fibre di collagene e ben ordinate, che come un’imbottitura riempiono il viso nel modo giusto.

Il collagene è una delle proteine della giovinezza: una pelle fresca, tonica e compatta ha abbondanti fibre di collagene e ben ordinate, che come un’imbottitura riempiono il viso nel modo giusto.

Ovviamente al nostro pescione non gliene importa niente di apparire giovane e bello: il collagene gli serve per sopravvivere.

Questo infatti è il segreto dell’incredibile resistenza della sua pelle ed è stato svelato ai raggi X, ottenuti dall’acceleratore di particelle Advanced Light Source del laboratorio di Berkley.

Gli scienziati hanno utilizzato la microscopia a raggi X, per ottenere un’immagine delle proteine a livello atomico. Così hanno scoperto che le fibre di collagene, quando vengono pressate e tirate come se venissero morsicate, ruotano su loro stesse e diventano delle micro scale a chiocciola.

Questi movimenti a livello molecolare aumentano la resistenza del collagene. Ecco perché il piranha rimane a bocca asciutta. Ora gli scienziati stanno cercando di realizzare materiali sintetici che imitino questo comportamento per realizzare tessuti di sicurezza più resistenti e leggeri del kevlar.

Never trust appearances. Natural phenomena studied by physics sometimes deceive common sense. For example, the light that illuminates these words hides a secret: it appears "white", it is actually composed of many colors. Or there seems to be firm and yet we move in the universe with a speed of hundreds of thousands of kilometers per hour. Or take the freshwater fish Arapaimas gigas also called pirarucus. It lives in South America, is one of the largest in the world and can exceed 100 pounds and reach 2 meters in length. In his fresh water, roam the piranhas, whose sharp teeth can puncture the leather or the bones as if they were made of butter. But pirarucus don’t fear bites of their colleagues, their skin could withstand up to a pressure equal to that exerted by a weight of 98 tonnes out of a single square centimeter. In practice, a double pressure than it can bear the hull of a nuclear submarine. Why? To unravel the mystery, a small sample of their skin was irradiated in a particle accelerator … Marc Meyers of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and Professor Marc Meyers of the Jacobs School of Engineering at the University of California at San Diego studied the skin dell'Arapaimas for nearly four years. And they have discovered how and why these big fishes manage to survive the most bad bites. First, the skin is not as soft as that of a trout but is covered with harsh scales, arranged like tiles on a roof. They are mineralized scales, similar in composition to the enamel of the teeth. This seems to be the secret. But the truth is submerged. The scales, such as a chocolate filling, hiding a soft heart. These filaments of collagen, a protein elastic and resistant, arranged in a particular way: Collagen is a protein of youth: a skin fresh, toned and firm has abundant collagen fibers and well-ordered, and as cushioning fill the face in the right way. Obviously our big fish do not care to look young and beautiful: it needs the collagen to survive. This is the secret of the strength of his skin and was unveiled to X-rays, obtained from the accelerator of particles of the Advanced Light Source at Berkeley Lab. Scientists have used the X-ray microscopy, in order to obtain an image of the proteins at the atomic level. So they found that the collagen fibers rotate on their own and become micro spiral staircases when they are pressed and pulled as if they were bitte.n These movements at the molecular level increase the resistance of the collagen. That's why the piranha remains… dry. Now scientists are trying to create synthetic materials that mimic this behavior to achieve safety fabrics more durable and lighter than kevlar.

Lascia un commento